No one contradicts Orson Welles. No one dares.

In 1938, Welles was the wunderkind of the broadcasting world with his company Mercury Theatre on the Air. He was the director of the (in)famous War of the World's Broadcast, which placed him firmly in the radio firmament.

Ora Nichols walks out of a rehearsal on Orson Welles. Ora Nichols, after being called a "crackpot" makes Orson Welles apologize . . . publicly.

Ora Nichols was the head sound engineer of CBS and was curating the sound effects for Welles' broadcast of a "desert play." She designed, created and performed sound effects. She used a "sand box" while the actors were walking, for ambiance. Welles took issue with the fact that this sandbox looked like a cat's bathroom. Welles fills the whole floor of the studio with sand from Coney Island. The sand fails, the mics pick up too much feedback. The "catbox"/"sandbox" returns. (1)

Welles was a "realist" director -- if a lawn was being cut in the radio play, there was a man with a mower in the studio. Ora, on the other hand, works in metaphor -- she knows a roller skate sounds more like an elevator door-grate than any real elevator-door grate can. She knows Argo cornstarch when pressed rhythmically, sounds like foot falls in snow. She knows that keys and nails suspended and gently clinking sounds like "magic" to a listener.

Ora Nichols, far left. March of Time broadcasrt

Ora Nichols had an uncanny sense for the medium of radio -- she rendered sound according to the imaginary associations of the listener. A jam jar opened in a toilet bowl? That's how she made the "martian cylinders" unscrewing in The War of the Worlds. She concocted and built a one-of-a-kind, giant-cube of a sound machine with pneumatic pumps, whistles and engines that could perform hundreds of sounds: gun fire to birds chirping.

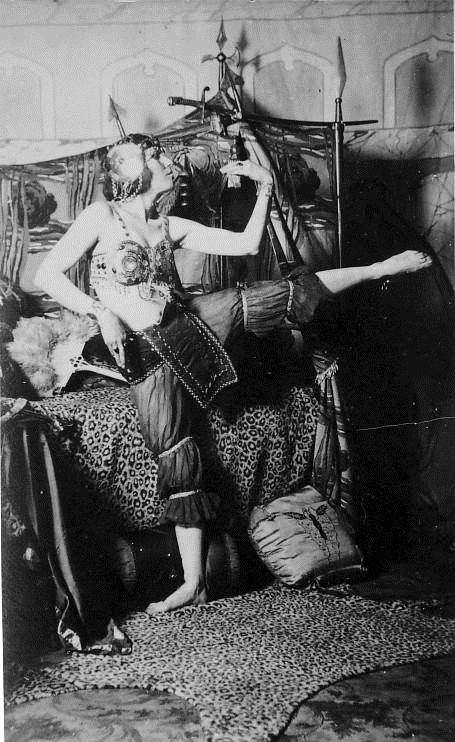

Ora Nichols on the Vaudeville Circuit, 1920s.

Ora Nichols came to radio by way of the Vaudeville circuit -- she was a dancer and a trap drummer. As times changed and technology advanced, Ora's medium changed. She ended up accompanying silent films with music and sound effects. And as the talkies came in, Ora again adapted, and began work in radio sound effects first as a freelancer and then eventually as the head of the department at CBS Radio. She lead the team on Mercury Theatre on the Air, The March of Time, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century and many others.

Even today, the internet's best guess is that 5% of all audio engineers are women -- Ora was certainly outstanding in many senses. She heard radio as a drama of both Space and Time. She understood "audio-positioning," namely that the ambiance of a room could be manipulated to give a sense of a hospital corridor or a cozy living room -- and our ears are fine-tuned to pick up on these subtleties. She heard that the relationship of objects and persons in the studio directly transferred into the ears and imaginations of the listeners. What she grasped is that the nation needed to develop a shared vocabulary of sound -- "effects standardization." No one knew what a hippo's mating call or a gun sounded like on the radio (or not even in daily life). They had to learn -- it was a new audio language with new signifies. This shared vocabulary then achieved a "sonological competence" and we were able to communicate in this new medium of sound fluently. (2)

Variety headline: January 1938. (Full article below)

Formal, in-depth research on Ora Nichols has never been compiled. This project is an exciting chance to uncover and tell her story. She began work in radio in the mid 1930s - the "Golden Era" in which radio was a new medium and the first type of mass media. Humans may not be the tool makers anymore, but we are the storytellers. We still have that need to gather around a fire -- except in this case the fire has been replaced with vacuum tubes. Radio is such a democratic medium. It have never happened before that a king or leader could be in your livingroom -- and suddenly FDR was chatting with you next to the fire. The diaphragm of the microphone is your ear. He is having a conversation with you, personally. Also, radio waves have a rare property: no matter how many tune into a broadcast, the strength and quality of the signal remain the same.

And my idea is to tell Ora Nichols' story using her language: About the Project & Performance.

(1) Mott, Robert L. Radio Sound Effects: Who Did It, and How, in the Era of Live Broadcasting, 2008.

(2) Verma, Neil Theater of the Mind, 2012.

*If you have not heard it, check out RadioLab's War of the Worlds podcast. It's brilliant (like everything they do).